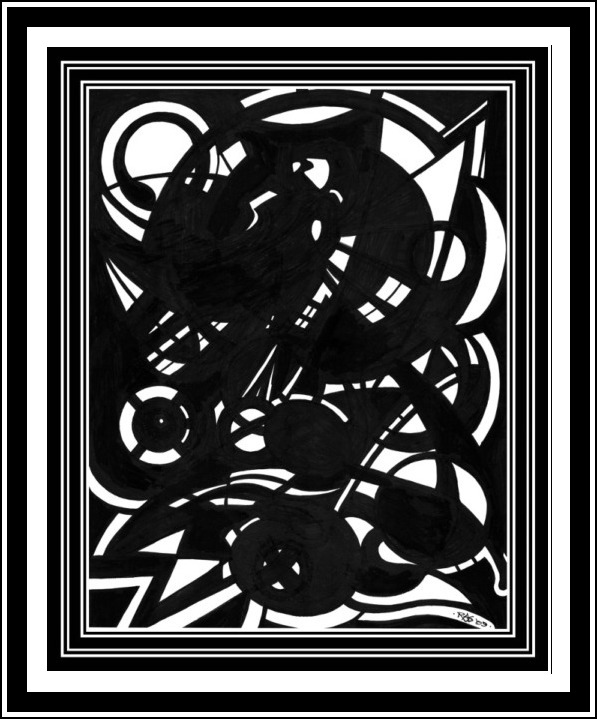

had been tormenting me

apparently

for a long fucking time

I tore her off of me and

slung her like a bag o’ dried snakes

to a crowd of some kind of ravenous things

maybe people

maybe not

also there

but on my side

apparently.

had been tormenting me

apparently

for a long fucking time

I tore her off of me and

slung her like a bag o’ dried snakes

to a crowd of some kind of ravenous things

maybe people

maybe not

also there

but on my side

apparently.

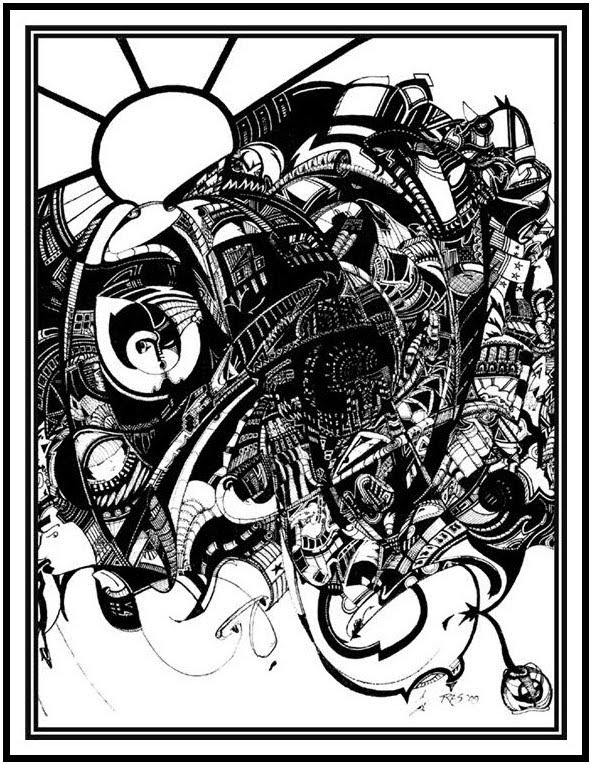

Joya Lonsdale’s My Mouth is Open to All Rivers opens with an ars poetica worthy of its dedicatee, Pablo Neruda. With her leading poem I cannot reside, unentangled, Lonsdale declares straight off her astonishing adhesion to all life’s stuff of edge and dream, and in a poem so easeful in its arching ambition, so lyric in its insistent indictment of our complicit crimes, that the reader is willingly enfolded in the soft creases of our (as she must see it) conjoined natures, and basking there, little suspects that within the mutable frame of these short and short-lined stanzas lie buried pungi stakes of inescapable fact. . . . massacres, unfettered by blood . . .births, fevers. Lonsdale says: I have cravings. and Lightening strikes me in places. She won’t say where.

But star-borne, yes, we are, and of the rocks and air, and as much of blood; but contradistinctwise, deprived by desire, depraved even, in result, and not just to the strange, but too, toward family and friend; we lament, can we escape ourselves, this world? Again, Lonsdale says it better and more plainly:

. . .

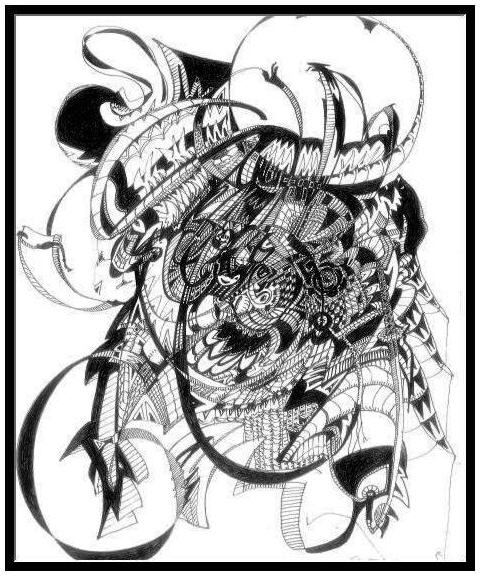

Sometimes, I admit

I become

empty of

breath and

long to

run away , untethered

by hands and feet.

I grow tired of my skin.

News accelerates my pulse . . . and things won’t leave me alone . . .

. . .

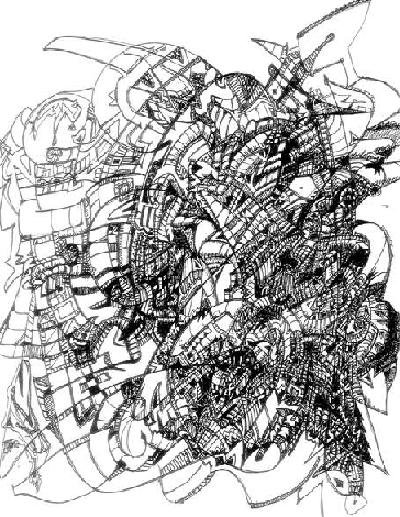

A grasshopper lands on my chest,

presenting his perfect form. . .

. . .

Because I have ears

two girls on a bus look at me and erupt into song.

. . .

Because my mouth waters

a fresh raspberry lands on my tongue

. . .

The ocean insists on crashing into rocks, and smelling salty.

I cannot escape the sand inserting itself coarsely between my toes.

I am here

clothed in human flesh

and I love.